Sponsor: Do you build complex software systems? See how NServiceBus makes it easier to design, build, and manage software systems that use message queues to achieve loose coupling. Get started for free.

I see the same two issues come up over and over with event sourcing — they cause a lot of pain and they shouldn’t have to. Most of the pain stems from bad modeling, specifically because of CRUD-Sourcing. In this post I want to show why long event streams usually mean you’re modeling the wrong events, and how to fix that so your streams have natural starts and ends.

YouTube

Check out my YouTube channel, where I post all kinds of content on Software Architecture & Design, including this video showing everything in this post.

The common problem: long event streams

Look at any discussion about event sourcing and you’ll find the same question: what do I do if my event stream never ends? I get it. I use a warehouse example in some videos where you receive product, ship product, and the events just keep coming. A bank account is the same — deposits and withdrawals forever unless the account is closed. That endless stream feels like a problem.

If you’re familiar with event sourcing you might be yelling SNAPSHOTTING. Yes, snapshots are an optimization when streams get long, and I’ll link to more on snapshots at the end. But snapshotting is not the first thing I’d jump to. Before optimizing, ask: do the streams really need to be this long?

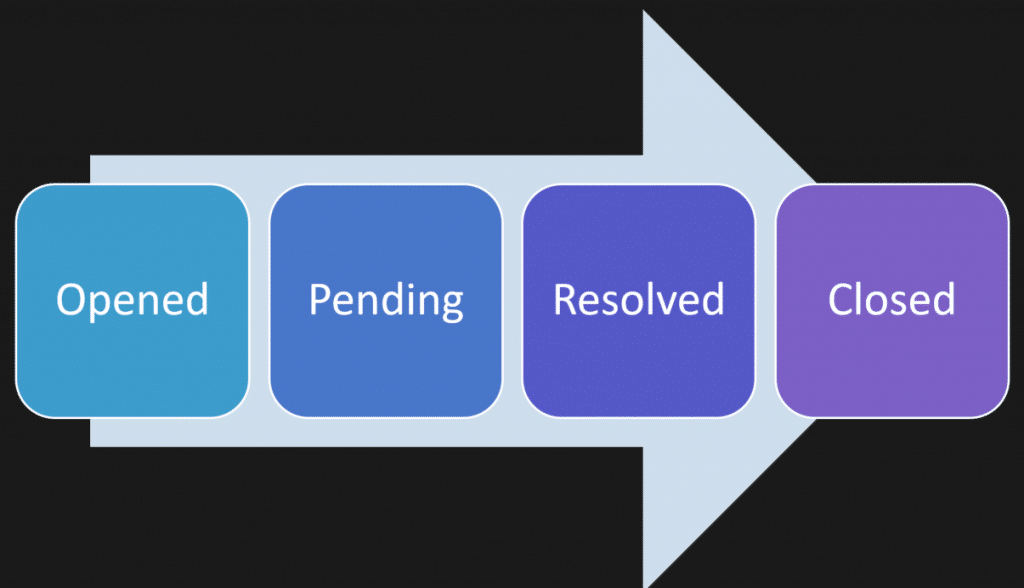

Most things have a life cycle

Most domain concepts you model actually have a life cycle — a beginning, a work in progress, and an end. A simple example is a support ticket. A ticket is opened, moves to pending as you work it, there are interactions, it gets resolved, and then closed if there are no further interactions. That gives you a clear start and end.

Even the warehouse and bank account examples have life cycles. You start receiving a product, do many operations, and eventually you discontinue the product. You open an account, have many transactions, and eventually you close it. The key is to find the natural checkpoints in those life cycles and treat them as boundaries.

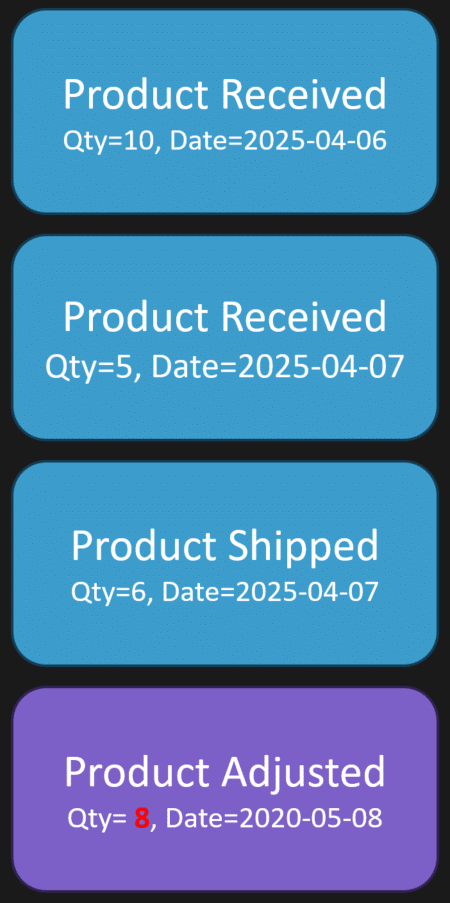

Stock count as a natural checkpoint

In the warehouse example, think about a stream that starts when you first receive a product at quantity 10. You receive five more the next day, so you have 15. Then you ship six, so quantity on hand becomes 9. Later you do a physical stock count and discover one is damaged or lost, so you adjust to 8.

In the physical goods world, the real source of truth is what is actually in the warehouse, not what the system says. That stock count and adjustment is a natural checkpoint — it marks the end of one stream and the start of the next.

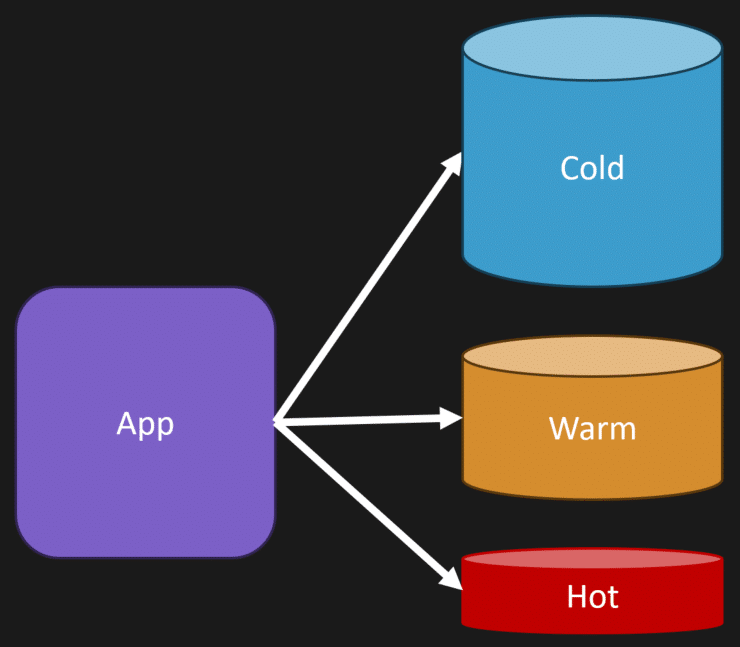

Cold data vs hot data and periods

Think about cold and hot data. Cold data is historical, rarely accessed, almost archival. Hot data is recent and accessed frequently for reads and writes. Many systems naturally partition by this idea.

A good real world example is accounting. Accounting operates on annual cycles. The chart of accounts itself is not the stream; instead you model the accounting period. The period gives you a bounded start and end for the transactions that belong to it. Use those natural boundaries when you can.

A common trap: CRUD-sourcing

One big reason people end up with long, unbounded event streams is they model events as CRUD changes, not as workflow. They capture property changes like “stop changed” without capturing what actually happened or why it happened. This is what I call CRUD sourcing or property sourcing.

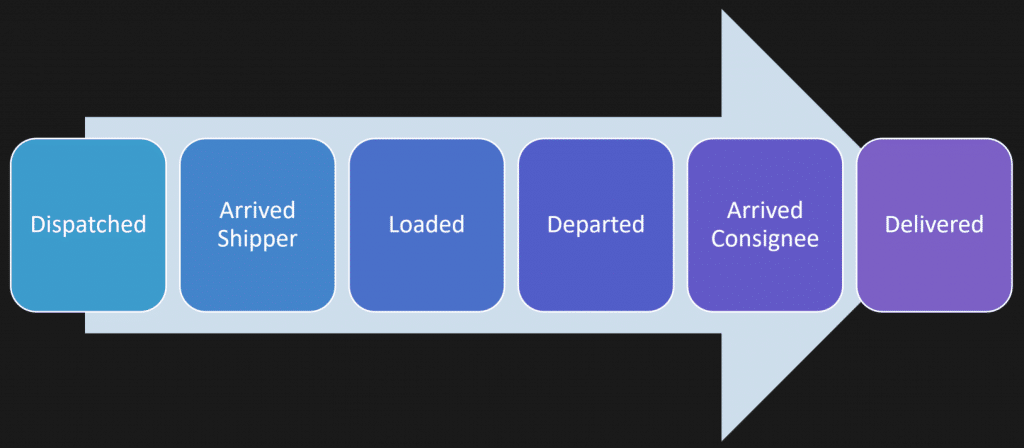

When your events are driven by change data capture tools and look like raw data deltas, you lose the workflow meaning. An event that says “stop change” tells you nothing about why it changed. You have to infer the reason. In contrast, workflow events explain what happened and why.

Compare:

- Stop changed — purely technical, ambiguous, no domain meaning

- Arrived shipper — specific, meaningful to the shipping domain; we know the vehicle arrived at the shipper to pick up freight

Workflow events give you the life cycle you want.

For a shipment you might have events like dispatched, arrived shipper, loaded, departed, arrived, concented. Those workflow events define a beginning and an end for that shipment’s stream. They are not a long series of undifferentiated property changes.

How to keep streams manageable

To avoid long event streams, focus on modeling the business processes you actually care about. Capture workflow events rather than raw property deltas. That often produces streams that are naturally bounded by life cycle events or by explicit periods.

If you still have high volume streams, there are several options:

- Make streams bounded by time or by business period — it could be a year, a day, or even an hour depending on your domain.

- Use natural checkpoints — stock counts, account closings, order completion — to mark the end of one stream and the start of the next.

- Use snapshotting as an optimization only after you’ve modeled events around workflow and periods. Snapshots speed up reads but don’t fix bad modeling.

When to snapshot

Snapshotting is a valid optimization for long streams, but it’s not the first thing to reach for. Ask whether your stream needs to be long in the first place. If you modeled workflow events and used boundaries and you still need better performance, then snapshotting is appropriate.

CRUD-Sourcing

In short: stop CRUD-sourcing. Model the why, not just the what. Look for life cycles, natural checkpoints, and appropriate periods to bound streams. Use snapshots as an optimization, not as a band aid for bad modeling.

Join CodeOpinon!

Developer-level members of my Patreon or YouTube channel get access to a private Discord server to chat with other developers about Software Architecture and Design and access to source code for any working demo application I post on my blog or YouTube. Check out my Patreon or YouTube Membership for more info.