Sponsor: Interested in learning more about Distributed Systems Design? Enter for a chance to win a 5 day Advanced Distributed Systems Design course led by Udi Dahan founder of Particular Software, and creator of NServiceBus.

You have some code that handles placing an order. This could be an HTTP API or a message handler. You made it idempotent. You added a unique constraint on some kind of message ID.

And somehow… you still end up double charging the customer’s credit card.

YouTube

Check out my YouTube channel, where I post all kinds of content on Software Architecture & Design, including this video showing everything in this post.

Idempotent

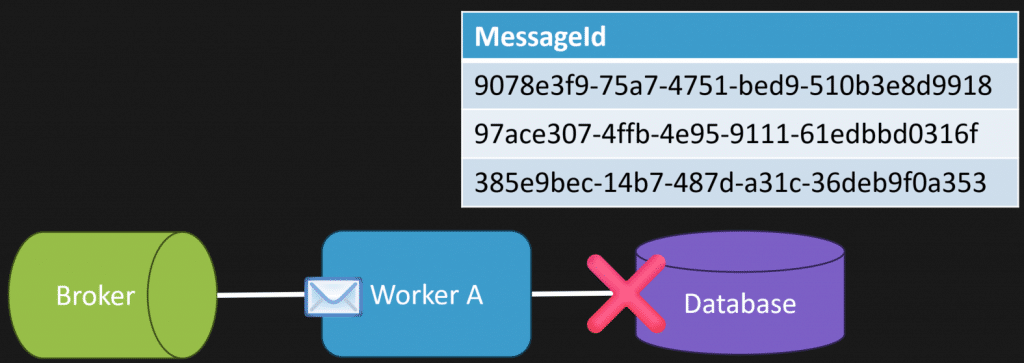

You did everything right. You have idempotency. You have an inbox table and a unique constraint on that message ID. Your handler should be exactly once, right? Wrong.

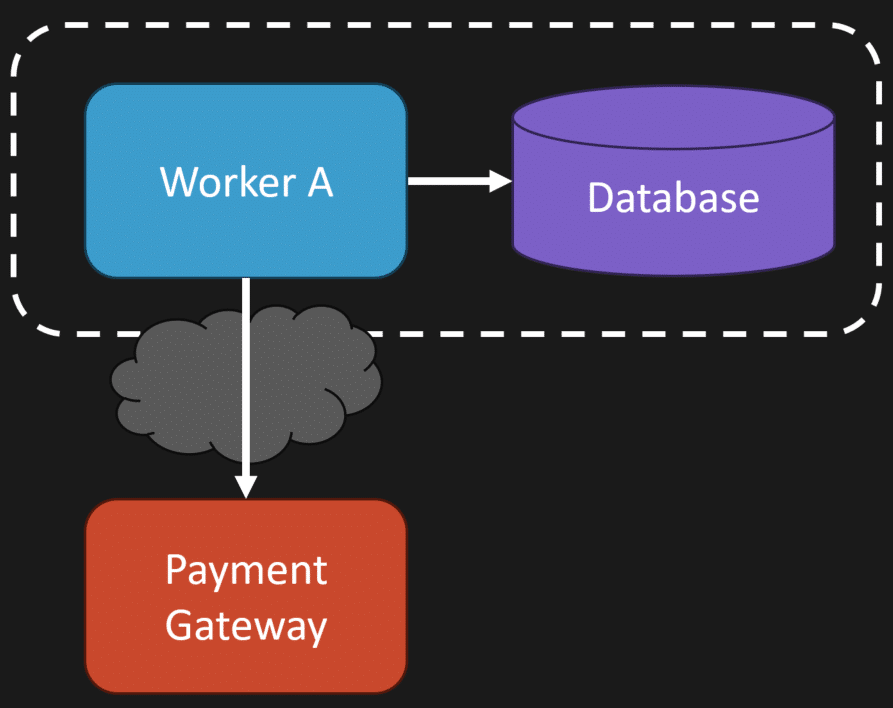

And it’s because of this call to our payment gateway outside of our database transaction.

Our database can tell us whether we processed the message, but it doesn’t stop us from double charging our customer.

So let’s talk about why this happens, how concurrency can make it worse, and some solutions.

The happy path: idempotency with internal state

Let’s say you have an HTTP API where you might get multiple requests from the same user. Or this could be a message handler from a message broker where a message can be delivered more than once.

What that looks like is:

- A request comes in

- We take a message ID and persist it to our inbox table

- Because we have a unique constraint, if it wasn’t there, everything is fine

Then that exact same message (or HTTP request) comes back in. Guess what? It’s already there. So our request fails.

This is the happy path. It’s idempotency inside the database.

As long as you’re only updating internal state, this works. But it gets a lot more complicated once you start calling something external… like a payment gateway.

Why the payment gateway breaks “exactly once”

In the happy path, all we do is:

- start a transaction

- add our message ID to the inbox

- persist state

- if it was a duplicate, we throw when we save or commit

Simple.

But we also need to make the call to the payment gateway. And this is where the issues start.

It might seem like a good idea to call the payment gateway immediately. Maybe you get a transaction ID back, some receipt, something you can persist in your database to mark the order as paid.

But here’s the problem: That payment gateway call is outside of our transaction. Outside of that unique constraint.

So now this can happen:

- First request comes in. We charge the customer. We save our inbox record. We persist our state. All good.

- Second request comes in (same message, same request) We charge the customer again. Then we hit the database and fail because of the unique constraint when we save and commit.

So our database protected our internal state. But it didn’t protect the external side effect.

Concurrency makes this easier to see

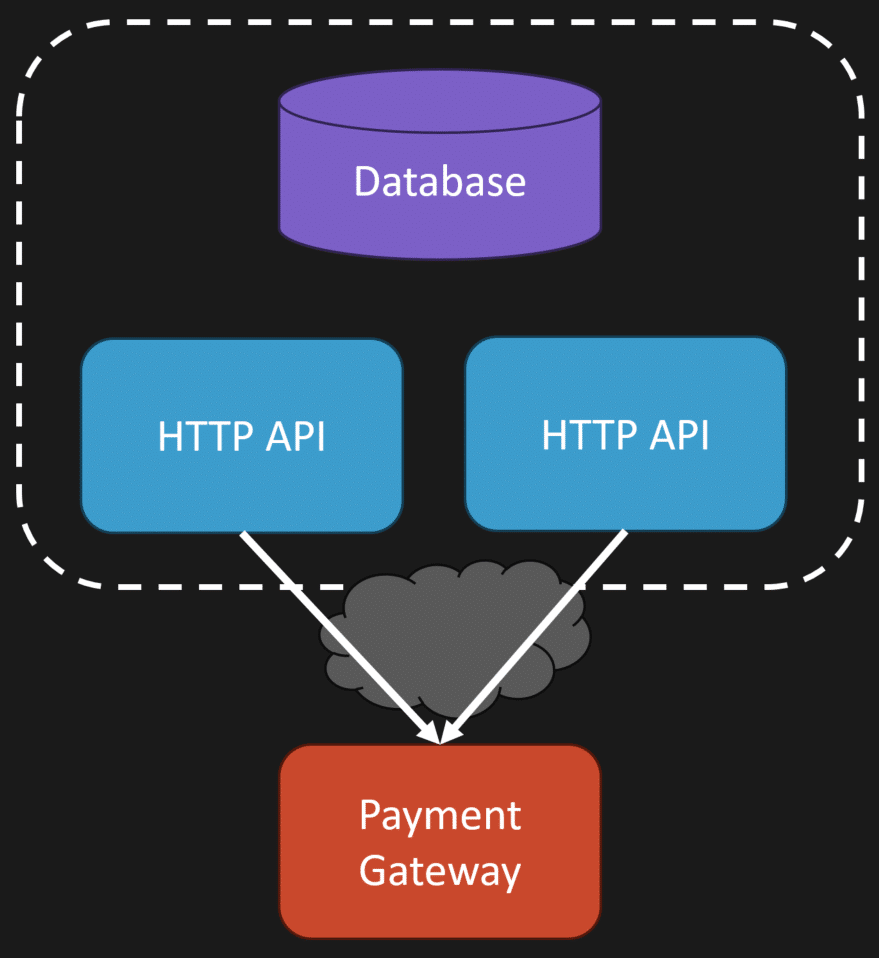

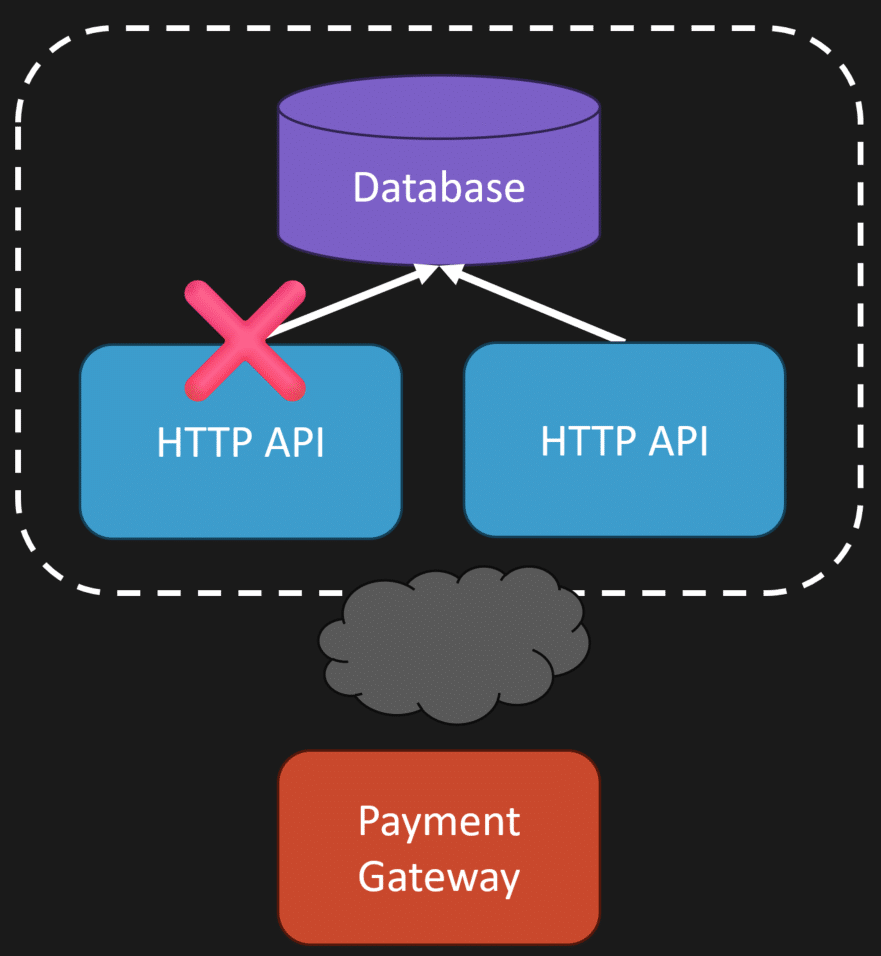

If you’re looking at this from an HTTP API perspective, you can have two identical requests come in at the same time.

The load balancer sends them to two different instances.

They both hit the payment gateway at roughly the same time.

One of them wins the unique constraint. The other fails on commit.

But both potentially charged the customer. At the start I said concurrency can make it worse. A different way to think about it is: concurrency makes it easier to reproduce and prove you have the issue.

There’s no magic distributed transaction coming

One “solution” is a distributed transaction. The reality is you’re not going to get one.

That inbox table protects your internal state, but the moment you cross that network boundary to the payment gateway, all bets are off. You kind of went from exactly once to at least once.

But we can design for it. There are a few approaches here. It’s not one magic fix. It’s usually a combination depending on your situation.

1) The third-party service supports idempotency

Your third-party service might support idempotent requests.

A good example is Stripe. It supports an idempotency key that you pass in the header to make idempotent requests.

So you decide what the key is for that specific business operation. If the same request happens more than once, you send the same key again.

Now it becomes idempotent on the payment provider side too.

Side note: if you’re creating an HTTP API, support idempotent requests. Your clients will love you. If you don’t, they’re the ones who have to deal with the rest of this stuff.

2) Lookup by a reference ID before charging

If the provider doesn’t support idempotency keys, another option is a lookup against some kind of reference.

In my example, I have a payment gateway and I want to know: is this invoice paid?

My reference at this point is the order ID. So the flow becomes:

- Ask the gateway: “Is order 123 already paid?”

- If not, charge it

You can still have race conditions here. This can still be an issue. But it may be good enough, especially if the third party has a unique constraint on something like your order ID.

3) Serialize the operation per business key (locking)

If lookup isn’t enough, another solution is serializing the operation by a granular business key.

What I’m talking about here is locking.

You’re basically creating a distributed lock. That might be:

- using your database and row locking

- using Redis for locking

- something else entirely

In my example, “granular business key” might be per order. That means only one payment attempt for that order runs at a time. If I can’t acquire the lock, I retry, or return something that tells the caller to retry. Now at any point, we only execute one at a time for that order, charge the customer once, and release the lock.

Caveats

The trade-off is throughput. That’s why the business key has to be granular. If you lock too broadly, you slow everything down.

Also, timeouts matter. If the payment gateway times out, that does not mean it failed. It might have actually succeeded. So even with locking, you still need to think about what “timeout” really means.

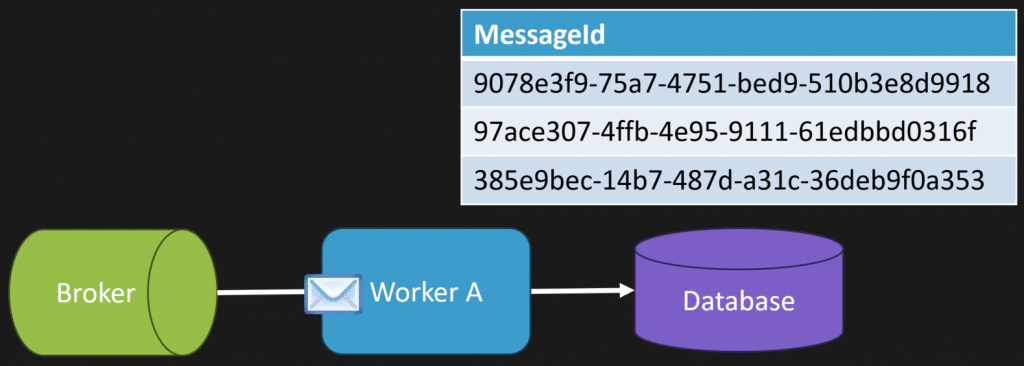

4) Separate internal state from external calls (inbox/outbox)

Another option is inbox/outbox and splitting internal state from the external call.

What does that mean?

- We get the order

- We mark it as payment pending

- We add a message to our outbox saying “charge payment”

- We save all of that together in the same transaction

Then separately, a processor reads the outbox and performs the external call to the payment gateway.

If the provider supports idempotency keys, that outbox processor uses them. And then if it succeeds, we mark the order as paid. This doesn’t magically fix double charging. You could still double charge.

What it does give you is better internal consistency and better failure handling, because message handlers let you handle retries, backoff, timeouts, and errors differently than your main request path.

That’s one of the reasons I love messaging.

5) Reconcile and compensate

This generally always happens: you need reconciliation and compensating actions.

There’s nothing wrong with this. If something realizes “uh-oh, we double charged”, you void or refund.

This can be a workflow step, or a periodic reconciliation process that compares your system with the third-party system. You’re not failing as an engineer because you need compensation. This is just reality when you’re dealing with external systems.

Putting it all together

You have a lot of options, and it’s often a mix:

- Use an inbox table to dedupe incoming messages

- Use a unique message ID to prevent reprocessing internal state

- Use an outbox pattern so your intent to call an external system is persisted with your internal state

- If the provider supports idempotency keys, use them

- If not, can you lookup by a reference ID to see if the action already happened?

- If acceptable, can you serialize with a distributed lock by a granular business key like order ID?

- And when those don’t cover everything, reconcile and compensate

Ultimately, I don’t think the goal is “exactly once” as in “the operation only ever happens exactly once.”

A better goal is designing a system that’s effectively once — it behaves correctly even when you deal with race conditions, concurrency, and timeouts that are outside of your control.

Join CodeOpinon!

Developer-level members of my Patreon or YouTube channel get access to a private Discord server to chat with other developers about Software Architecture and Design and access to source code for any working demo application I post on my blog or YouTube. Check out my Patreon or YouTube Membership for more info.