Sponsor: Interested in learning more about Distributed Systems Design? Enter for a chance to win a 5 day Advanced Distributed Systems Design course led by Udi Dahan founder of Particular Software, and creator of NServiceBus.

In a recent video I did about Domain-Driven Design Misconceptions, there was a comment that turned into a great thread that I want to highlight. Specifically, somebody left a comment about their problem with Aggregates in DDD.

Their example: if you have a chat, it has millions of messages. If you have a user, it has millions of friends, etc. It’s impossible to make an aggregate big enough to load into memory and enforce invariants.

So the example I’m going to use in this post is the rule: a group chat cannot have more than 100,000 members.

The assumption here is that aggregates need to hold all the information. They need to know about all the users. But that’s not what aggregates are for!

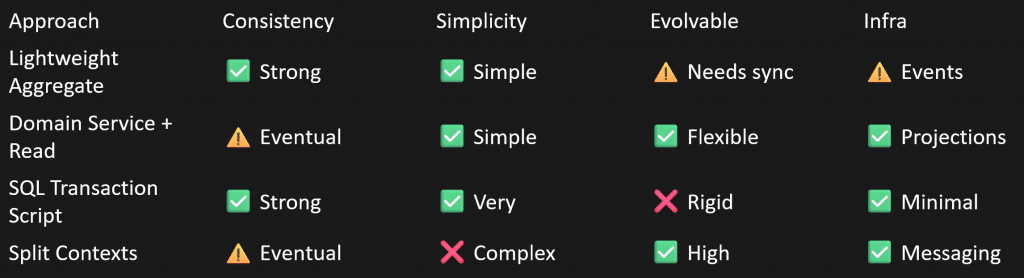

I’m going to show four different options for how you can model this. One of them is not using an aggregate at all. And, of course, the trade-offs with each approach.

YouTube

Check out my YouTube channel, where I post all kinds of content on Software Architecture & Design, including this video showing everything in this post.

The Common Starting Point (and the Trap)

So this is how people often start with aggregates in DDD, which is directly what that comment was talking about. Say we have a GroupChat class. This is our aggregate. We’re defining our max number of members as 100,000. And then we have this list, this collection of all the members, all the users associated to this group chat.

Now, this user could itself be pretty heavy in terms of username, email address, a bunch of other information, and maybe some relationships with it.

Then, for our method to add a new member, all we’re doing is checking to make sure we’re not exceeding 100,000, and then we throw.

This is where people start. But here’s the problem with it.

It may feel intuitive, but it’s a trap. It’s a trap because you’re querying and pulling all that data from your database into memory to enforce a very simple rule.

The big mistake here is: we’re modeling relationships, not the rules.

We’re building up this object graph rather than modeling behaviors.

Option 1: Store Only the Count

An alternative is to just record the number of members of the group chat. That’s actually the rule we’re trying to enforce. We don’t need to know who is associated to the group chat. We don’t need to know which users, just the total number so we can enforce the rule.

The obvious benefit is we solved the problem: we don’t have to load all those users into memory. This is going to be very fast.

The trade-off is if you do need to track which users are part of which group, you’ll have to model that separately.

Option 2: Enforce the Rule Above the Aggregate

Another option, if you feel storing a count is too risky because it could get out of sync, and you’re already recording which users are associated to which group, is to push the invariant up a layer, above the aggregate, into some type of application request or application layer.

Here I’m using some kind of read model or projection to get the number of users. Because it’s a projection, it could be stale. That’s the trade-off. Then we enforce the invariant there. If we pass, we add the user to the group chat.

A fair argument here is: “Well, really? We have some aggregates enforcing invariants, some application or service layer enforcing invariants, everything scattered everywhere.” But reality is: you have to enforce rules where you can do so reliably, not where it always feels clean and tidy in some centralized place. That’s not reality.

An aggregate can only enforce a rule if it has all the data it needs. And often your application or service layer isn’t just a pass-through. It shouldn’t be. It’s doing orchestration, gathering information and deciding whether a command should be executed.

Option 3: No Aggregate At All (Transaction Script)

This might sound surprising, but you don’t actually need an aggregate at all. Sometimes I advocate for using transaction scripts when they fit best.

That’s what I’m doing here: start a transaction. Set the right isolation level. Interact with the database. Do a SELECT COUNT(*). That’s going to be very fast with the right index. Lock if needed. Check the invariant. Insert the new record. Commit the transaction.

Simple.

Sometimes a simple problem just needs a simple solution, and a transaction script is very valid.

The trade-off here is if you’re in a domain with a lot of complexity and a lot of rules, this can get out of hand and hard to manage.

Option 4: Model Rules, Not Relationships

Another option I mentioned earlier is: stop focusing on relationships and focus on the actual rule.

What makes us say the group chat is the one that needs to enforce the rule? Maybe there’s actually the concept of group membership, and group chat is about handling messages. These have different responsibilities.

That’s really what I want to emphasize: you don’t need one model to rule them all. You can enforce something in one place and something else somewhere else. You can have a group membership component enforcing whether you can join, and group chat is just about messages.

There are all kinds of approaches you can take, and they all have different trade-offs. Given the rule and how you’re modeling, pick what fits. It does not need to be an aggregate just because dogma says so.

Maybe it’s a transaction script. Maybe it’s an aggregate. Use what fits best.

When you’re modeling something like the group chat example, start with the rule. Ask yourself: Where can I reliably and efficiently enforce this rule?

Not: “How can I convert this schema into my object model?”

Too long didn’t read/watch: model rules, not relationships.

Join CodeOpinon!

Developer-level members of my Patreon or YouTube channel get access to a private Discord server to chat with other developers about Software Architecture and Design and access to source code for any working demo application I post on my blog or YouTube. Check out my Patreon or YouTube Membership for more info.